The Korean Conflict or was it a war? As of this day over 8,000 US servicemen are listed as missing.

I was with the 88th Military Police Company (Corp) when we went ashore, in Hungnam Harbor, 27 Nov 1950. We had arrived on the SS Ainsworth and debarked via a cargo net into waiting LCMs (Landing Craft, Men). Our company headed north to Hamhung, where we established our headquarters in tents.

Two major events took place; the Chinese entered Korea and the Manchurian winter came with them. Along with the cold, minus twenty degrees, came the snow. Our clothing was the same as you would have found in any garrison in the USA. The exceptions were the pile jacket, and my field coat had a pair of experimental leggings snapped inside the coat. They could be unsnapped, lowered and then zipped down over the leg to provide an extra layer of cover. Without those items we couldn't have survived.

We slept on the ground on top of Oriental mats made of cotton in summer sleeping bags. One of our duties was to guard supply dumps. No one had to tell you to keep moving, because to stop moving in that three hour period meant death. The cold weather stayed and so did the minus twenty temperatures. On one occasion I had been exposed for three hours and when I returned to Hq (headquarters), I decided it was time to brush my teeth. I removed my canteen from its canvas and felt pouch, and when I attempted to pour the water, found that it was frozen solid.

During this period of time the Marines and others, who had been cut off to the north, were making their move south. I was assigned, with Jeep, to the 1st Marine Div, under a Lt Landrum. That lasted for about a week. North of Hamhung the Marines had set up a CP (Command Post) to gather their flock together. I saw, time and time again, six or ten Marines checking in and that was all that was left of their companies. Any serviceable vehicle was usually towing two or three others. Almost every vehicle had the windows shot out by machine gun fire and holes all over the truck bodies. Serving with the Marines had completed my odyssey. I had now served in or with the four branches of service shoulder to shoulder during combat operations.

A long, long time later I read a book called CHOSIN, which was written about the withdrawal. It told about one group of a thousand Chinese, who were forced-marched, to cut off the Marines. They were found later frozen to death in their foxholes. Only about two dozen had survived. The cotton uniforms had gotten wet with perspiration and the cold, cold weather did the rest.

We moved back to Hungnam, into billets that had been for the workers in the industrial complex there. Here, we discovered a new enemy, bed bugs. How they survived the cold is a mystery of nature. One night there I developed diarrhea. It was after dark and no latrine facilities had been set up yet. I got away from the billets by walking up the hillside. As I did my thing, projectiles passed overhead which sounded like a flight of bathtubs. I then heard explosions in their direction of flight. It turned out to be the 16 inch guns of the Battleship Missouri, which was sitting on the Sea of Japan providing cover for us.

That day we learned that the Chinese had infiltrated our former campsite. We now spent time keeping the MSR (main supply route) to the harbor open. The Marines were being sent back south and the harbor was the only way out. The Chinese had cut all roads south. We were now committed to twenty of twenty-four hours a day. Finally we moved onto an LST (Landing Ship, Tank) and that was to be our home until Christmas Day when we departed and the harbor was blown up. The noise was terrific. Our artillery was positioned on the beach, the cruiser Rochester, the battleship Missouri, plus destroyers were on the Sea of Japan. They rained shells on the enemy day and night. Many of the shells were short fused and went off overhead and when that happened you checked for holes and continued your work. I did hear that our shore-based artillery did fire seven thousand rounds over us in one night.

The perimeter was now only three miles. By day you could see our airplanes attack the hills with bombs and napalm. By 1950 our armed forces had been pulled (reduced) down, including the merchant marine. Where would the ships come from to effect our rescue? The Japanese would come to our rescue. We had supplied them with landing craft and other ships after WWII. The Japanese merchant marine responded with ship and crew to fill our need. These were the people who had fought us tooth and nail just five years before. It is truly an amazing world.

We withdrew, by LST, our destination in South Korea was Ulsan. As we left the harbor, that Christmas Day, we had a lot to be thankful for. We had no Christmas dinner and we did have seventy tons of ammunition on board, but that didn't matter. We listened to the Armed Forces news broadcast, from Japan, giving the Christmas dinner menu, tom turkey and all the trimmings. We ate our can of C rations and hoped we wouldn't take a hit. We would get our turkey dinner days later.

Note: Ammunition and troops together are a no, no, but circumstances alter courses. We would start north again and the Marines would re-troop, regroup, and re-equip within Korea, a task that I thought was not possible. They would be on the line once again. Our unit would receive the Meritorious Unit Commendation, for that period of time, by Dept of Army, General Order, No 41, paragraph 6, issued on 21 April 1952. Signed by J Lawton Collins, Chief of Staff.

The 88th MP Company (Corps) had come from Ft Jay, Governor's Island, NY. Their port of debarkation was Seattle, Washington. They were fifty men under strength and they hoped to get their replacements at Ft Lawton's replacement center. Their request was forty-nine short as I was the only one available there. We departed Seattle 7 Nov 1950.

It was Christmas Day, 1950. We had crossed the Pacific, debarked at Hungnam, headed north to Hamhung; only to be forced to withdraw by the Chinese intervention. I classify it as a withdrawal and not a rout because the troops had thrown their equipment away, but retained their weapons. We were now headed south on the Sea of Japan. Our seventy ton of ammunition had been loaded in a hurry and had not been shored. As a result the load had shifted and some shells had fallen into various voids. The shells were not fused and had been in their individual canisters, so it wasn't a problem. A couple of days later we were at Ulsan Harbor, which is about thirty miles north of Pusan.

We would start north again and I would be on the move until January 1952. The moves would have a see-saw affect, as the battle lines moved back and forth. Each move was a story in itself. My story will take you to villages with the names Kwang-ju, Andong, Tanyang, Won-ju, Songsan-ni, Inje, and finally Kobangsan-ni. I would depart Inchon Harbor on 10 Jan 1952, not knowing that I would return to that port again on 14 Feb 1962, for peace time duty.

My .45 cal pistol was stolen in the final days at Hungnam. I was sleeping in a bunk on the LST, and had hung my pistol and rifle on the bunk. I awoke to find my pistol missing, so I reported it immediately. I was told that it would be written off as a combat loss. Four months later I was handed a statement of charges by the EX officer. He said that they had forgotten to follow through and I would have to pay. I remembered my days of Counter Intelligence (CIC) training, so I told him that I would not sign, but would request a report of survey. It would be months before they would send an investigating officer from Corps, but it would be written off.

We set up a police station in the 500 year old city hall of Ulsan. My platoon sergeant almost made history there when he tried to start a fire in a stove with a ration can full of gas. Fortunately the flames subsided and the only damage was a scorched ceiling. During the time we were there, the guerrillas attacked a National Police outpost. The chief had no gasoline for his vehicle, so he asked our captain to provide transportation. The captain declined and I started to wonder what our mission was. Several days later, one of our patrols found a full 55 gallon barrel of gas. I got permission to give it to the Chief, so he would have the gas he needed. Several days later I asked the interpreter what the chief's reaction was to the gift. The interpreter looked at me and said, "You played a big joke on the Chief". I asked him what he meant. He told me that I had given the Chief a barrel of human excretion. Now we were in trouble, so I got permission to make up for the mistake by giving the Chief five gallons a day until he had the fifty-five gallons. It was time to leave.

The company moved to another small village, and I was only there for a couple of days before I was moved north with an advanced platoon. The winter was still with us when we moved into Andong. I met a 16 year old Korean school boy named Jun-Bum Lee. He wanted to learn English and in the little time I had I tried to help him. The lines moved forward and so did I. I did give him my parent's address and through that, years later, we connected again.

Darkness had fallen and we circled our sleeping area with our Jeeps, because we had been told there would be tanks maneuvering into position. An enemy unit was moving toward our area. It was snowing as we crawled into our sleeping bags. I removed my shoepaks and the felt insoles. I covered the shoepaks with my helmet to keep the snow out. My insoles went into the sleeping bag with me, so they would dry out. In the morning we dusted off the snow and prepared for the defense of Andong. The frost was 20 inches down and we had a hard time digging our foxholes. I tried tossing a hand grenade in to break up the soil, but all it did was explode up and out with little effect. The enemy unit by-passed us and continued south.

One night I was asked to recon a blown-up road bridge, east of the town. It was pitch dark, but I crawled over the bridge to see if it was possible to by-pass it. I was up on the structure when some one yelled "Chung gi", I hesitated and continued checking. The words again, but this time I heard the rifle bolt go forward and that is a universal language. I couldn't see my challenger, but I knew I had better act fast. I figured it wasn't the enemy, or my throat would have been slit by now, so I shined my flashlight on the markings, on the front of my helmet, and said, "MP". That worked, the soldier came forward and we conversed by using drawings, which he responded to with other drawings. I even learned that their Japanese trucks had no four wheel drive and that explained why they were having so much trouble on the icy roads.

No one but the enemy traveled the main supply routes (MSR) after dark. One night we had a request to escort a signal corps unit north thru the Tanyang Pass. I was one of the three lucky ones. An MP in the front and rear vehicle and one on a truck in the center of the convoy. It was thirty miles to the foothills and then another 14 miles through the pass. We had gotten to the foothills and started up before we were challenged. A soldier stepped in front of our truck lights and the first impression was that he had a lot of courage. We heeded his warning and stopped. Lucky for us because his back-up was composed of a company of south Korean troops.

We proceeded to the north end of the pass and there we stayed to take over the control of the traffic through the mountain defile. Our platoon came forward and we set up in an abandoned school building. The yard was occupied by a dead Korean, so two of us buried him, while the sergeant played Taps on his harmonica. We used candles for lighting, but they were usually in short supply. I scrounged a light bulb and socket. I could hook the light to discarded signal corps batteries. They had several voltages and by jumpering the voltages, I could use the light bulb. I could now write my letters home with little effort. My platoon leader saw me using the bulb hook-up and I was told to discontinue its use. Was he jealous? I'll never know. He was the same officer who I'll bring up later, using the booby traps.

Our truck had a .50 cal machine gun on a ring mount, on top of the roof. This was a good place to test fire it. We found that it would only fire one shot at a time. Later, back in the states, at Camp A P Hill, Virginia I would be one of the noncoms selected to find out why a reserve unit, in field training, was having the same problem. We were to discover that these machine guns were pulled from Air Force stock and that they had a special timing device, in the buffer plate, to increase the rate of fire and it had to be set perfectly or the gun would fire only one shot at a time. This modification had not been in US Army manuals.

During this period of time the Chinese had hit the left flank and had rolled back the Korean 8th (ROK) Division. We established a straggler point to allow rearward movement only by those who should be going to the rear. I was up in the pass when the 8th ROK was being brought back to regroup. They were on foot and were carrying their machine guns and mortars. They were cold, worn out, hungry and tired. A soldier carrying a mortar base plate slipped on the snow and ice, and before he could get to his feet, his sergeant kicked him and he went down again. I had learned the first couple of bars of the Korean National Anthem and even though I can't carry a tune, I stood up in the Jeep and I sang their anthem. The result was unexpected, faces lit up, their stride picked up and they all started singing. The troops front and rear picked up the song and the mountain vibrated with their singing. Our next stop would be Wonju.

Wonju had changed hands seven times in eight days. The enemy would overrun a mortar position and turn it around and then it would be retaken again. We moved into Wonju to control the pass over the mountains south of there. The village had a crossroad in the center of town. That area was flattened like a pancake. There was a partial wall standing where the bus station had been.

REQUIEM FOR A SOLDIERYou left your home and family to answer your country's call much as I did, too. You, a Chinese soldier, suffered the cold and privations of war. In 1951, you battled for Wonju, Korea. The town changed hands many times in a few days. As the battle raged you paid the supreme price. Finally, your side gave ground and Wonju became ours. Had we met at a different time and place and under different circumstances, I know we would have been friends. I found you and your comrades that day when I noticed wild dogs feeding on you and the others. I shot some of the dogs and the others ran away. I reported your location as you would have done for me, and you and your friends were buried. "Rest in Peace, soldier." Note: In October 2001 I was given a New York Times newspaper, dated 24 January 1951. An article in that newspaper said Wonju changed hands seven times in eight days. -RWR- 6 June 1996 |

A good time to explain our duties. These roads and mountain passes were previously used by ox carts. They were unpaved and not very wide. We had to control the flow of traffic, so as to allow the flow north or south, but not at the same time. Vehicles moving north had the priority if the front line wasn't withdrawing. The decision was firm, line troops moving forward, to backup the line, had priority and ambulances to the rear had none. I saw times when the troops moving forward, did so for the better part of a day and the ambulances with the wounded sat until there was a break.

The MSR was closed when darkness fell. In the morning we moved south to take over the pass, we discovered wild dogs were eating the dead lying there. I don't know if they were Koreans or Chinese, but we did shoot the dogs. I reported the incident and they were eventually buried. I was in the pass one day with a flat tire. When a truck approached I flagged it, so I could get assistance as I had no spare. It had been used the day before for another flat. As I talked to the truck driver my attention was turned to his cargo. In the back was a pile of dead GI's, three deep. They had been recovered from the battlefield. It was a revelation; all those guys had names and had belonged to someone, and now they were nobody, only a number. At a later date that number would be translated back to a name for burial. Freedom doesn't come cheap, someone pays the fiddler.

I had a recall to active duty in, prior to leaving the states. I did not get it. Here I was serving as a Corporal and had a reserve commission as a First Lieutenant, MPC. Officers with no active duty were being called to serve and we were to get one. A nice guy from New York State. He couldn't even read a map. I took him under my wing, and in a round about way, he learned. He didn't lack intelligence and he did realize what I was doing. The enlisted men didn't have a whiskey ration, but the officers did. He always passed me part of his ration. It was like gold. A bottle of whiskey could be purchased at the Army PX in Japan for a couple of dollars. Here it was worth fifty dollars.

We had a good mess sergeant with our platoon and he could do more than cook. He had found an old Korean crock and had gotten the ingredients to make what he called "raisin jack". It had to ferment for a while and then it became an alcoholic beverage. It was so good that the platoon leader discovered it by smell, and knowing his troops, turned to the mess sergeant and told him to get rid of it. We did, but you could only drink so much at a time.

The same officer had the area loaded with booby traps and I took him to task and was firmly put in my place. Several days later I heard the muffled, "boom, boom" and I knew what happened, but I didn't know to whom. He had gotten two national police in one of the booby traps. The officer was later removed from duty, but wound up at one of the rest camps, in South Korea. See, screw up and get recognized. At Wonju, I was one of the company to be General MacArthur's body guard on his visit there. I even got to salute him as he passed my check point with General Almond. North to Songsan-ni.

At Songsan-ni I was in the tent police station. It was there that I met a movie actress visiting the MASH. It was Piper Laurie. I had my picture taken with my arm around her, but the officer transferred before I got a copy. Here also, I ran into Hemmoragic Fever. It was carried by the fleas on rats and mice and was usually 100% fatal. We were more afraid of it than the enemy, because you couldn't see it. On one occasion a truck driver came by to see if I could find where his convoy had gone. He said he had become ill and had lost them. As I made a call on the phone, he dropped in front of my desk. MASH sent an ambulance and he died there the next day. The fever had struck again.

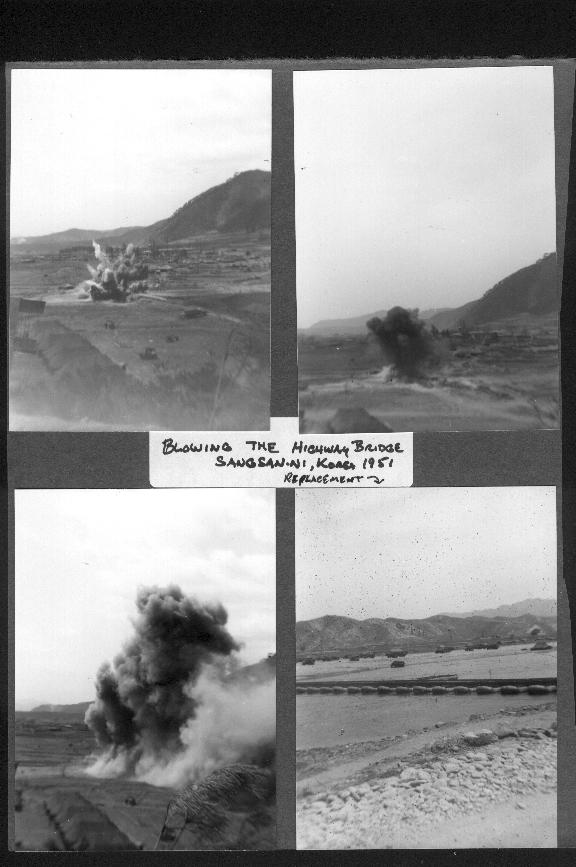

The Chinese started an offensive and we had to withdraw again. There was no time to dismantle the Bailey Bridge, north of town, so it had to be blown. I got my camera and went up the hill for a better shot. It blew; the engineers must have been determined to do a good job as I spent the next few seconds dodging boulders as they rained on my position.

The enemy pressure subsided, and I was moved to a forward position to control the movement of troops back to their former sectors. They had been moved to their present positions to turn back the enemy offensive. I had a squad of men and we needed tentage for the night. I located a MASH unit and asked them for shelter. No problem, because they had some men at rest camp, but they would be shy two beds. We could use the auxiliary morgue as it wasn't occupied at the time. They gave us two stretchers, which we placed on the ground. It was cold, so we both pulled the blankets over our head and went to sleep. I was awakened by a noise. There were two people and the one discovered the "bodies" and commented on the MP helmet and the other one said, "I guess he was the one they brought in yesterday. He must have died". I heard one of them go through the pockets of my jacket, which I had hung on a packing crate. I was going to wait until he was about to give me a body search. Then I would make him a believer by grabbing his hand. It was not to be, because my MP sat straight up and they almost fainted. I doubt whether they would do that again, but I was sorry I didn't get to use my idea as it would have been more effective.

We were starting to pick up quite a few Chinese Prisoners. One of them appeared to be in his 20's. He had good field clothing, including sunglasses and was carrying two rifles with ammunition. He seemed to expect the worst. I put him at ease through our Korean interpreter and he relaxed. I tagged him and he was sent to a processing unit. North again, this time to Inje.

At Inje the Chinese had taken a pounding and had retreated. I had one of their donkeys for a while. When I sat on his back, my feet would touch the ground. I would ride him down to the river, get a much needed bath and ride back. The unit was having trouble getting reports back from Kobangsan-ni, so I was sent there. It was a crossroad under enemy observation. The Lieutenant was a former sergeant with a devil may care attitude. That was the reason he was there. They shipped another sergeant in, who had gotten as far as basic infantry and they kept him there until he had five stripes. No field experience and no military police experience, only the infantry school books. I ran the tent police station here and this guy was like a fifth wheel, but the ranking noncom. One night I was on guard duty, with my M3 machine gun, when he came out and started harassing me. I took a lot, and then told him his lot in life and if he didn't go inside and leave me to my job, I was going to kill him. I guess there was no doubt in his mind, because I wasn't bothered after that night or reported.

At the crossroad we had a straggler point and one day they picked up a man named Ashcraft. I called his unit, learned he was AWOL. His first sergeant came to pick him up and told me he was glad to get out of his tent as they had just stitched it with bullet holes. A day or so later I received a call from Ashcraft's first sergeant. He told me that Ashcraft had been put in a forward position and had deserted, and if I saw him to shoot him. He got by our check point and weeks later I was in another sector, at a MASH unit, when a soldier, thinking I was a 2nd division MP, said, "Boy, they really gave it to Ashcraft". I asked him what happened, and he said they had tried him and had given him twenty years at hard labor.

I was on road recon, one day, and happened by an artillery emplacement. One of the sergeants said they were about to have a fire mission and if I desired I could pull the lanyard on one of the guns. That sounded good, but then I heard they were having steak for lunch. Lunch arrived before the fire mission, so I had my steak and the fire mission ended before I was finished. Now you know my priorities.

On another road recon, one morning early, I had gotten to the top of the mountain, south of our camp. There was a heavy frost and my windshield coated with it. I stopped the Jeep and we proceeded to remove the frost, when we came under fire. We were in the Jeep and departed there in a hurry. I selected the long way back and good I did, because they ambushed a signal unit we had passed. It took me a long time to get back to the foot of the mountain, where I alerted the infantry unit there. By the time they responded the enemy had disappeared.

I had the necessary points to go home and we were into the second winter. We had to travel by truck to the railhead at Chunchon. The roads were snow covered and narrow. We had three minor accidents on the way there. On to Inchon and by ship, to Japan, for the trip home. I had some close calls that weren't the result of enemy action. The vehicle accidents were routine. On one of the withdrawals, the vehicle up front tossed a white phosphorous grenade over the bank, but it hung up and went off close to the road, dropping some pieces on the hood of our Jeep. At the airstrip one of the fighters fired a rocket toward us during take-off. At an MP check point they decided that a stump was in the way and blew it as we came along. Our Jeep started to float away as we forded a flooded river. A weapon's carrier washed away shortly thereafter at the same spot.

I have written this forty plus years after the fact from memory and hope anyone reading it, who was there, will forgive me if some of the dates and places don't mesh. On the road patrols and recons I saw various things of interest and all though I remember them I can't recall the area. There was one place I remember quite well. I was sent on a road recon, off the beaten path. I entered an area that hadn't seen war in recent times and probably looked the same way centuries ago. It was quiet and rural, almost like entering a different world. I drove up a mountain road and was surrounded, on all sides by a panorama of valleys and mountains. Still no sign of war. I knew, as I looked north, that there was action there and as I listened carefully I could hear the sounds of artillery coming from that direction. As soon as I returned to the MSR, I had returned to the real world.

On another recon I had entered a valley as the sun was coming over the mountains. On the hillside were huge grass covered mounds. It was a burial ground for important people a long, long time ago. The sunlight caught an object that I thought was a brightly colored vase. The head moved and I realized it was a ringneck pheasant (native to Korea). I took aim with my carbine, fired, and it dropped. It was a change from combat rations.

When you controlled a defile (one way road) you met everyone coming and going through that area. A cold winter day we were trying to get the 3rd Division forward, into a blocking position, along the MLR. I was at the south end of the defile. The road went into the mountains and the roads were snow covered and slippery. Those four-wheeled vehicles that made the grade, were winching the others through the pass. This took additional time and as a result they were not in the forward position that they were to occupy. My next visitor was General Ruffner, the division commander, and he wanted to know why I hadn't gotten the vehicles through on time. I looked him straight in the eye and said, "If your vehicles had chains, they would have cleared my position two and half hours ago." He dropped his head, turned away and said, "Yes I know, we don't have the equipment".

The Jeep was a wonderful vehicle. I had used them in WWII, civilian life and here they were doing the job again. Our company had entered North Korea with their proper equipment and that included 24 motorcycles. Due to the winter weather conditions they were swapped at ordnance for Jeeps and never left their crates or the harbor area.

Note: Back in the states they found they had many sergeants there, who had never been overseas. They cleaned house and sent them over to Korea. They couldn't put them in infantry companies, because they would have caused a revolt. My company had very few sergeant positions and everyone had been busting his hump for a promotion. Now, there would be no promotions. Several of these sergeants were assigned to our company and the morale was hurt. Some of the men, who had been with the company from the start, were talked into staying longer for a promotion. I met some of them years later and found they had stayed in vain.

During 1951, while serving with the 88th Military Police Company (Corps), I submitted a request for helicopter training. My first sergeant had told me of the program and I had the necessary pilots' license and flying time.

In July I was ordered to Tokyo to take the physical. I went to Japan using my set of orders and decided to stay out of military control, because that way I could stay out of a precise date and time of return to my company. Well, there I was in Tokyo, with the same field clothing I wore in Korea. I met another GI who had on the proper uniform and we got into a taxi. After a lot of pigeon English, the taxi driver understood my need for a class A uniform. He drove down some back alleys, stopped at a shack where they did laundry, came out with the necessary uniform. The size was OK, but the service cap had a band emblem on it and I didn't have the necessary collar brass to complete the uniform. We directed the driver to the PX and my friend went in and came out with the necessary insignia. We paid the taxi driver for the trip and the clothing and we were on the streets of Tokyo.

Some enterprising young man found out we wanted a hotel room and that led to another taxi ride to another section of the city. I can't remember the name of the hotel, but I know the section of the city was the same name as the hotel. Ryukyu or something similar. The room was nice. The entrance way had a running fountain in it and beyond that was a room oriental style (rolled mats on the floor) and the next room was stateside with a regular bed. The hotel was owned by one of those huge Japanese wrestlers. The only time I wore the uniform was to go for the physical and to leave Japan. The rest of the time I went native and wore a kimono. The bar had plenty of good local beer and the menu was good, but some of us heard they had frogs for sale in the Ginza (shopping market) and we sent one of the guys to buy some. He returned with them, but the cook looked at them with disgust and wouldn't cook them. He did let one of the GI's use his kitchen and so we enjoyed eating our frogs.

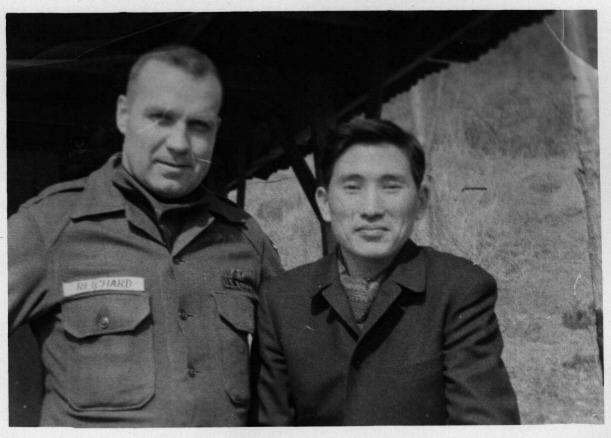

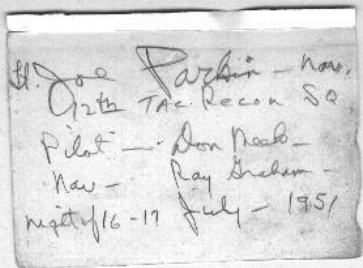

A couple of days after my physical I said good-bye to Japan and headed back to Korea. I flew into Taegu and there were no immediate flights to the front areas. I walked into AF operations, 12th Tac Recon Sq, talked to some of the fliers and found out I could hitch a ride on one of the photo recon missions. Having been down the path in WWII, I checked the operations board and selected a crew with over 10 missions. I located the pilot (Lt Don Meek), 12th Tac Recon, and he gave me the OK, time and place.

I was there and got the co-pilots seat. There were two other crew members: Lt Joe Parkin and Lt Ray Graham, both navigators. I'm sure that only one did the actual navigation and the other handled the electronics. The plane was called a B-26 (old A26). We were on our way. It was a beautiful night. As we headed north, we passed over an invisible line called the "easy line" and all navigation lights were extinguished. My being there was to prove the anti-aircraft wasn't as intense as I had experienced in Europe during the great war.

Well it wasn't too long before a barrage of AA shells exploded in front of us. They burst high and that saved the day. The pilot immediately took evasive action and the next barrage appeared in the position where we would have been if he hadn't changed course. I found out that our photo target would be of an area in the North Korean capitol.

Before we got there I noticed hundreds of vehicles moving south. Now, this was the time peace talks were started for the first time and I felt if they were to be meaningful, this wouldn't be happening. The reason I could see the vehicles was as they were driving along, in the dark, the drivers' had their lights out, but from time to time they had to turn them on to see the road. So, as a set of lights went out the driver 3 or 4 back had to turn his on to see the road. Therefore, from our position it appeared to be one long string of lights. Out of the darkness there appeared a parachute flare and in the light of the flare I could see our planes dive down to bomb and strafe the vehicles. The pilot told me this was called a "Firefly Mission" and the flares were being dropped by a C-47 circling above. At our altitude I could see three such operations going on at one time.

We went on the photo run, which was similar to a bombing mission due to the fact you held a steady altitude and attitude for a long period of time to keep the camera level. Our light, for the camera, was 8 nine hundred thousand candle power flash bombs. They were trained down and went off one by one. They lit the whole sky. In fact, I thought, what an easy mission, but as we turned away I could see the puffs of AA hanging all along our course in the moonlit sky. The flash of our photo bombs was so intense I didn't see the AA burst.

We continued on north with the intent to cross into China, but the border was socked in with heavy clouds. The pilot did spot a stranded train and did call for fighter assistance, but all he received was a thanks and the fact they were too busy with other targets. As we turned to head home one of the officers asked the pilot to go home low level to see how much automatic fire they could pick up. When the pilot declined, due to a head cold, I could have shook his hand, because I'd seen enough.

We landed safely with no more surprises. I did get the pilot to acknowledge my flight, in writing, because who would believe me when I returned to the company. As I turned to leave, he called me back and offered me a drink from a bottle of whiskey and said, "You earned this tonight". I still have the card with the names of the crew and the date.

Looking back, if I had been shot down, I would have been declared a deserter and God only knows if and when the proper facts would have cleared me.

My unit the 88th Military Police Company (Corps) supported front line troops in Korea in 1950. In those days most people thought of the Military Policeman as one who controlled the main gate of a military camp, directed traffic in the camp, and patrolled the nearby communities to check on the behavior of servicemen. They also visualized him in a freshly laundered uniform adorned with well shined brass, a leather Sam Browne belt and pistol, the white covered service hat, an MP arm band on his left arm, and short white leggings covering his spit shined shoes.

The above was true in the States, but not while assigned to Korea. We wore fatigues and field coat and we were identified by an arm band and the letters MP on the front of our steel helmet. Initially we carried the standard .45 cal Colt pistol, 1911-A1, but in North Korea, when we were switched to a reserve infantry unit, we were issued M-1 rifles and bayonets and they would be carried for the rest of our time in Korea along with our pistol.

Most of the time I was away from the company working in a platoon or squad in direct support of the infantry. We gave priority to supplies and men moving forward to the front lines and to the road movement of units sent to back up the lines when they faltered. We ran road recons to keep up with the present and future needs and on bridges to check the possibility of using fjords to by-pass them if they were too small or had been destroyed. We provided day by day locations of units to be able to direct convoys safely to them. If I ran the company police station, which was a tent with a sign out front along the MSR (main supply route), we investigated rape and murders as the line troops moved forward. It was almost impossible to locate the soldiers involved in instances such as those due to the anonymity and the language barrier. Even with an interpreter we would wind up with the translation of "chocolate soldier" in several instances and that would be the only clue.

As darkness fell the MSR was closed and the countryside belonged to the enemy forces who were still behind the lines. Each build-up area along the way became a strong point during the hours of darkness. At times we had to dig in to help in the defense of an area when a large force was moving freely behind the lines, be it day or night.

Most of the time we patrolled in a jeep alone and controlled defiles with a single man in the middle of nowhere. Sometimes the passing infantry would ask me where my backup was and when I told them there wasn't any, they usually responded by saying, "Better you than me." We set up a police station (tent) in front of the artillery about 2 miles from the infantry. We would check civilians moving south and also our own troops to make sure they were authorized away from their line unit. On one check I shook down a Korean and found a Russian burp gun in his blanket roll. He was immediately turned over to the Korean military. On a different occasion I turned over a Korean who was a spy for the other side. Later on I saved a "blue boy" who was one of our line-crossers, but by the time I got to him he had received rough treatment in the hands of our infantry and was lucky to be alive. His only ID as a spy for our side was that the 3rd button down on his white civilian jacket was sewn on with specific colored thread. I was privy to the information identifying these line crossers and the infantry wasn't. Those line-crossers had a lot of guts and every time they returned they put their life on the line, because they first had to get through enemy lines and then through ours before they could be identified. They were the true Korean Patriots and the information they brought back was invaluable to our intelligence services.

When we were setup near the infantry, the road coming from the north had signs letting drivers know that they were under enemy observation and they should not stop there. It was natural for drivers to move through this area with their foot on the throttle. I was told to setup a speed trap along that road to cite drivers who were going too fast. Once again I got into hot water by voicing my objections. That order came from an officer who was stationed about 20 miles south and that was the only time he visited our area. Speed citations were written but in time pressure from others stopped it.

Signs, which were meant to helpful could work the other way. On the top of one mountain pass was a sign on the descending, winding road which read, NOT A MAN IS ALIVE WHO TRIED THIS CURVE AT 25. Well, to most it was a challenge and challenge it they did. As a result many vehicles went off the road and rolled down the mountain, leaving the driver dead or severely injured. As I look back, this could have been the section of road where the speed trap was to have been setup and that would have made sense. It was on the same road, but further south and I'll bet the wrong site was selected. The resulting number of accidents, deaths, and injuries would have called for preventative action.

As the enemy gave way our lines moved forward and we picked up Chinese soldiers who had been left behind when their units retreated. The ones I processed were well equipped. They were young and one had two rifles and ammo with him. He was scared because he had been told we would kill him if he was captured. My Korean interpreter was directed to assure him that we would not harm him. We put a POW tag on him and he was sent to the rear for further processing.

Somewhere along the way a Korean officer had given me a Russian burp gun, so I carried it as it gave me more firepower. After a visit from a rear echelon officer I had to get rid of it. When I would travel to our main company headquarters they would check my jeep for standard equipment and remove those items that weren't standard. I had found a hydraulic truck jack and other useful items, but they confiscated them. Thereafter I hid the items if I went to the rear. I did manage to keep an M-1 rifle and carbine in my Jeep in addition to my .45 Colt automatic. We were never allowed canvas tops on our jeeps because they were afraid we would be attacked by the Chinese Air Force, so the winters were murder, especially the first one there. I guess the Jeeps finally got heaters in them, but not for the first and second winters while I was there. On 10 Feb 52, I left "The Land of the morning calm", not knowing that I would return in Feb 62.

The following information was obtained from the Military Police Professional Bulletin, PB 19-00-2, November 2000.

The final casualty rate for MP was 54 killed in action and 151 wounded in action. That was a total of 205 men out of over 42,000 who served on the Korean peninsula. Considering the hazardous situations in which MP were placed, the casualty rate was minimal. Those hazardous situations not only included guarding 200,000 POW, protecting critical locations and supplies, supervising the movement of over 100,000 refugees, and directing traffic on the battlefield, but they also hunted North Korean guerrillas, cleared roadways of enemy troops for troop and supply movements, protected convoys, fought as infantry troops, and exposed themselves to artillery and mortar fire.

COPY

|

| Table of Contents | Previous Page | Next Page |