Bob Reichard, on a 1,000 pound bomb which was dropped

four hours later on the multi-track railroad bridge at Augsburg

It was the day after Christmas, 1944 and we knew the night before that we had been scheduled to fly today. I was happy that we didn't have to fly on Christmas day, because I thought of it as a day of peace, regardless of what was happening in the world.

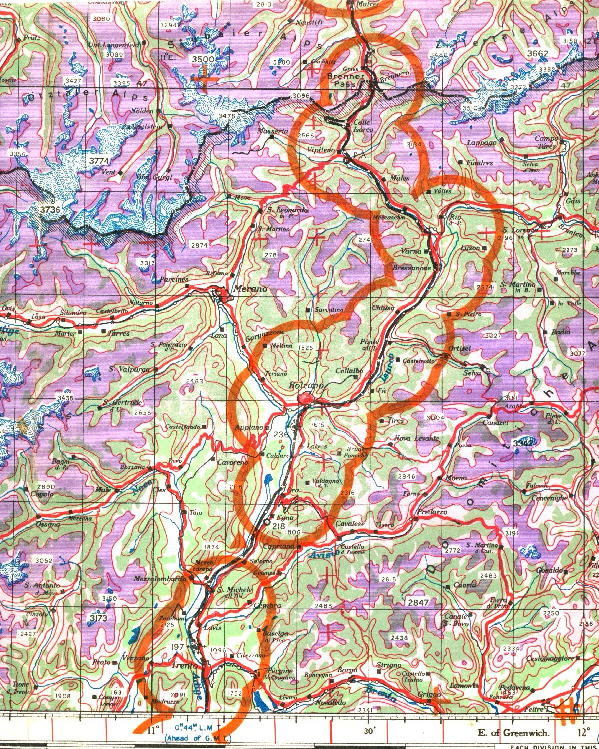

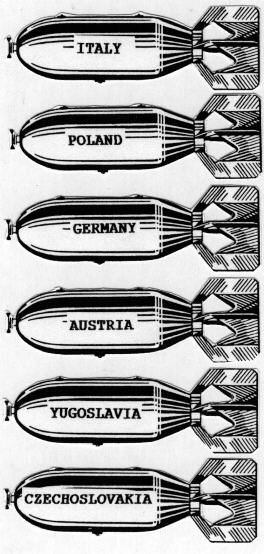

We were up long before daybreak and it was a cold morning. As we entered the briefing room there was a lot of excited conversation. I looked at the briefing map and the course line went through Austria, Czechoslovakia into Poland. The target was the synthetic oil refinery on the Oder River, at Oswiecim. It was going to be rough for more reasons than one. We would be over enemy territory for a long time and the distance was about the limit of our fuel supply. We would be in the air over eight hours, a longer time than I had spent in the classroom in my school days.

Our group formed and we headed north, making landfall at the north end of the Adriatic Sea. Austria was blanketed with snow and looked cold. I was cold and I looked at the thermometer and it was at minus sixty degrees. It was usually around minus forty or fifty, so now we had to put up with the unusually cold weather. I had on long wool underwear, my wool shirt and pants, covered by my heated flying suit, and my flying jacket and pants on top of the rest. Heated gloves and boots made it bearable, but not comfortable. On all our missions I gave the request for oxygen checks about every fifteen minutes. In the cold weather you had to make sure your oxygen mask had not frozen up. When I asked for the check, the entire crew responded with an OK starting with the tail position forward. The reason for the oxygen check is to give us a chance to check on anyone not responding, as death comes quickly and silently at the higher altitudes.

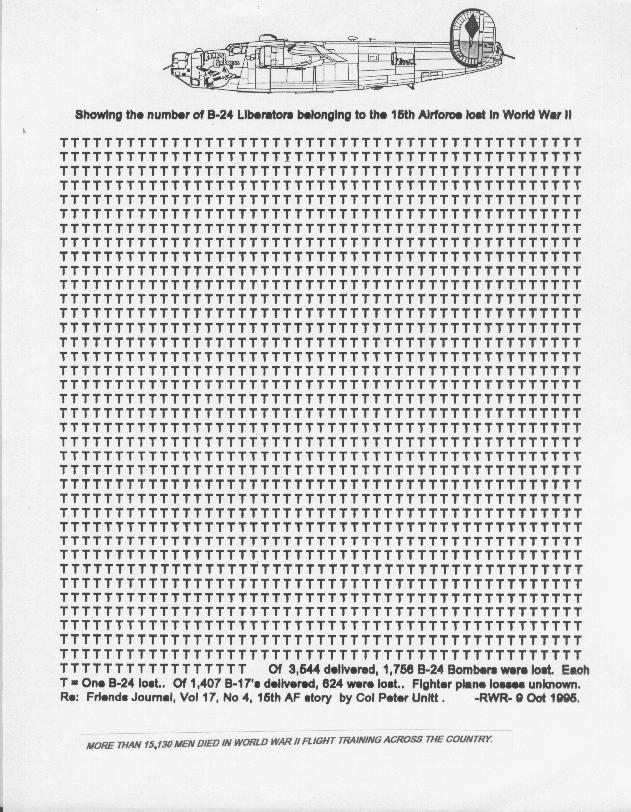

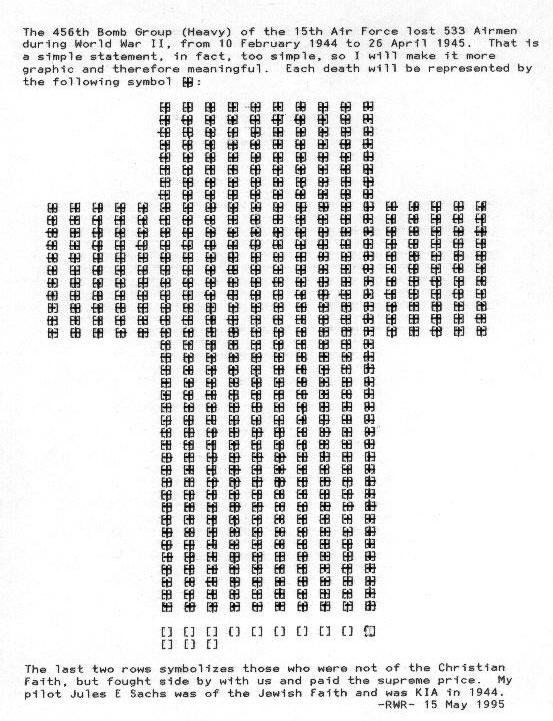

Happy day, there was no fighter opposition and we silently thanked our escort fighters because they did a good job. The flak was heavy, intense, and accurate. Twenty one planes attack the refinery and nineteen were headed home. Somewhere out there were the twenty airmen we left behind. I hope they parachuted to safety, but that wasn't usually the case. We survived the flak and returned safely.

I never had the idea that I was invincible and didn't ask my God to spare my life. I did ask him if I got hit not to do it halfway because I didn't want to linger for the usual two to three hours it usually took to get medical assistance. I did pray nightly as I was brought up to do, and a woman from the Lehighton area, by the name of Hawk, did send me the 91st Psalm, which I read every night at that time.

Why target Oswiecim? That haunted me for many years until I learned that Oswiecim is another name for Auschwitz. I believe the raid was to tell the people in that murder factory, to hang on because the war would be over soon. I have to believe that some of them smiled when the bombs hit the refinery.

On 4 January 1945, our target was a road bridge north of Verona, Italy. The area was south of the Brenner Pass, so it was well protected by anti-aircraft guns. Our path in and out was over the least number of guns. We dropped our bombs on the bridge. Our B-24 took a hit and the pilot was hit. In the excitement he pulled the plane out of formation and into an area of concentrated anti-aircraft guns. I saw a battery of guns fire on the ground and I know we were the ones targeted, because we were the only bomber in that air space. The pilot wasn ’t wounded, because his Flak jacket stopped the shell fragment. I got his attention on the intercom and gave a hard right correction. He responded and turned the plane. The shells burst harmlessly off to the left and high. I kept up directing him to the left & right until we were out of their range. We landed at one of our fighter strips behind our front lines, so the pilot could assess the damage to the bomber.

My alertness in seeing the FLAK batteries fire, and realizing that in seconds those shells would be exploding around us, getting the pilot’s attention quickly to change course, was the difference between me writing this today and getting shot out of the skies in Northern Italy that day. I’m sure that my action saved me, the crew and the plane, but that action was never put on paper for an award.

Remember, it would have to be the pilot to make the recommendation and he did pull the plane out of the formation. Who could blame him, because he had been hit. At that time he didn't know that the FLAK vest, had contained the fragment.

He would later recommend me for the Distinguished Flying Cross for my action on 20 Dec 1944. For some reason or other the paperwork didn’t get to the Colonel until 13 May 1945. The war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945 and at that point everyone wanted to get home. I didn’t receive the award and when I was getting out of the service in 1945, a personnel clerk, found the recommendation, removed it from my file and handed it to me, because he thought I would like to have it.

Here is that recommendation:

R E S T R I C T E D

HEADQUARTERS

456TH BOMBARDMENT GROUP (H)

APO 520

13 May 1945

SUBJECT: Awards and Decorations.

TO : Commanding General, 304th Bombardment Wing (H),

APO 520.

Transmitted herewith is a recommendation for the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to the

following named officer of this group:

1ST LT. ROBERT W. REICHARD 0-777934

s/Thomas W. Steed

THOMAS W. STEED,

Colonel, Air Corps,

Commanding

Incls:

1-Citation

1-Narrative

1-Rec. for award

R E S T R I C T E D

COPY

R E S T R I C T E D

PROPOSED NARRATIVE

AWARD OF THE DISTINGUISHED FLYING CROSS

On 20 December 1944, First Lieutenant Robert W Reichard participated as a bombardier of a B-24 type aircraft in a high altitude bombing mission over the strategically important Skoda works, Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. On the bombing run Lieutenant Reichard, in testing his equipment, discovered that the bomb bay doors would not operate electrically or hydraulically. Stationing the navigator at the bomb release switch in the nose and instructing him to toggle and salvo the bombs when the rest of the formation dropped, Lieutenant Reichard promptly proceeded to the bomb bays to see if he could open the doors manually. With complete disregard for his own personal safety, notwithstanding the fact that his ship was then at 24,000 feet and accurate flak was bursting around the formation, he began to wind the bomb bay doors open. He succeeded in opening two of the doors, and was valiantly trying to open the other two when bombs went away, tearing the two doors which had failed to open. Lieutenant Reichard then unwound the two untouched doors and by dint of great effort managed to get the other two torn doors together. These he wired back into place in order to help reduce the drag on the plane for the long trip home. By his unselfish devotion to duty, beyond the normal requirements of the job, Lieutanent Reichard was instrumental in securing an excellent concentration of hits on the target and by getting the broken bomb bay doors up in normal position he gave vital aid to his pilot in making the return trip with a low gasoline supply. By his professional skill and courage, as evidenced throughout his twenty-five (25) combat sorties, Lieutenant Reichard has reflected great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States of America.

R E S T R I C T E D

COPY |

The action took place 20 December 1944. What was left out of the narrative was the fact that a parachute was not worn during this action, because of the limited space and the manual action required. A walk-around oxygen bottle was necessary, too.

It is also interesting to note that the recommendation was signed by Colonel Steed, on 13 May 1945. The war in Europe ended 8 May 1945. Time to go home!Returning from another mission and nearing our base everyone relaxed. That was until we noticed many, many explosions south of our base on the ground. My first thought was,"How did the enemy manage to get behind us?" We landed and learned that the 464th Bomb Group storage dump was exploding. Some bomb handlers had gotten lazy and decided to roll the bombs from the body of the truck to the ground. One was sensitive and when it exploded the others were exploded by sympathetic detonation. It caused a large number of deaths and damage.

On 16 Feb 1945, we attacked the airport at Regensburg, Germany. It was the base for the deadly ME 262 Jet fighters. Our group carried 30 pound fragmentation bombs, in clusters. Each bomber carried 180 of the bombs. Once underway I thought about the target and it reminded me of a kid walking down a lane, pole in hand, discovering a hornets nest, striking it with his pole, knowing full well what the results would be.

Prior to the target the bombers formed a "frag front". This lined up the bombers wing tip to wing tip, 28+ across. As the aiming point on the ground was reached, the bombs fell, by clusters of six in train, which allowed a great coverage of the area in front of each bomber, as a farmer sowing a field with grain. As the clusters fell from the bomb bay, the bindings gave way and each bomb was freed. The opposition was not heavy and was limited to flak. Photographs showed damaged planes. In 1957, I was a paratrooper with the 11th Airborne Division, in Augsburg, Germany. I had a weight loss problem and went to the dispensary for a check-up. Due to the shortage of military doctors, the Army had hired a German doctor. We talked and I learned that he had been the Flight Surgeon for the ME 262 Group, during the attack, in 1945. He wasn't talkative, but did say that the group was no longer operational following the bombing raid.

At night we would go out and "borrow" stone fences from the Italians. One night we even received gun fire for our efforts. We armed ourselves with "Tommy Guns", but the opposition was gone when we returned. The stones were used to build a suitable club for our enlisted men. The big day came for the grand opening, but the officers were not invited since it was an EM club. That evening some of the crew came by to invite me, but I declined since it was off-limits to officers and told them as much. They said, "No Problem" and removed my insignia. At that point my OD uniform was the same as theirs. I entered the club and was enjoying myself when I spotted Col Williams of Wing intelligence. He knew me because I was the assistant squadron intelligence officer and had been in his company before. His guest was Doris Duke Cromwell (I believe she was the richest woman in the world at that time). He introduced me and asked me to join him. I told him why I was there and he had a good laugh. About that time Doris Duke received a proposal of marriage from one of the enlisted men, saying he wanted to marry her for love and not for money. With that she was escorted to a safer area.

We were returning from a mission to SE Europe, in late February 1945, and our course took us close to Maribor, Yugoslavia. I noticed a lot of rolling stock in the railway marshaling yards there. During the after-mission interrogation I passed on my observations. On 1 Mar 45, the target was the marshaling yard at Maribor. As we approached the target, there was a company of Ukrainians, fighting on the side of Germany, headed into the town, on its withdrawal north. The captain leading that group, on horseback, realized that the town was about to come under attack, so he stopped outside of town. How did I know this? In Nov 1956, I was in charge of the TAPS (traffic accident prevention section) in the American sector of Berlin, Germany. That captain had joined the US Army, as a SP4 , and was the TAPS photographer. In our discussions we confirmed the time, date, and place.

On 27 Feb 1945, our target was a large railroad bridge at Augsburg, Germany. The Flak was heavy, intense, and accurate. They were using the very heavy 120mm Flak and not the usual 88mm. The white smoke was our indicator and we knew the killing radius was about twice that of the 88mm. A bomber in the flight in front of us took a hit in the waist and the bomber broke in two. The front spiraled to the ground and the tail seemed to maintain level flight. In fact, the lead pilot had to swing our flight off course to avoid a collision with it. In 1956 I headed the Provost Marshal Investigative Section of the 11th Airborne, in Augsburg. The interpreter I used there was a US Army SP4. He had been on the AA guns as a Hitler Youth the day of my mission. My duties took me to the downtown police station and there I met many German Policemen. When I was in uniform I wore my decorations, which included my bombardier wings. On one occasion a German Policeman asked me about my wings and when I explained, he said, "I guess you bombed Augsburg?" And when I gave a truthful reply, he told me that he could tell me the date of the raid, as that was the day his parents house disappeared.

I returned to Italy in 1965, but this time I was stationed in the north and not the south, as had been the case during WWII. I made many Italian fiends there. They had suffered greatly during the war and had lost loved ones. My only missions to Northern Italy had been to knock out a road bridge north of Verona and several in support of the 5th US Army lines, so I knew I wasn't responsible for their grief. I didn't wear the bombardier wings there, because I didn't want to turn my new gained friends against me or open any old wounds. While there, in 1968, I turned in my retirement papers. My first overseas assignment had been Italy and it would also be the last.

27 February 1945

Another day of war for the 456th Bomb Group (B-24 Liberator Bombers), located in Southern Italy near the village of Storana. Selected crews of the four squadrons had been briefed and were in the sky overhead forming and gaining altitude.

On the scheduled time they headed north over the Adriatic Sea towards their target (Mission 207), which was rail transportation facilities including the many tracked railroad bridge crossing the Lech River, at Augsburg, Germany.

Hours later the target was in sight and we turned from the initial point toward the target at around 26,000 feet. Huge white bursts of anti-aircraft Flak appeared in our flight path. White bursts, not the usual black bursts told the crews that the Germans were using their biggest Flak guns and not their usual 88mm guns. We knew the killing radius was about twice that of the regular 88’s.

The first group dropped their bombs, as did our 745th squadron behind them. Something got my attention and as I looked ahead and off to the right I saw that a B-24 had the tail blown off of it. The front part had dropped off to the right and was spiraling toward the ground. The tail maintained level flight and our squadron was directed away from it so we couldn’t collide. I did not see any parachutes.

The war in Europe would end on 8 May 1945 and soldiers , airmen, and sailors would return to civilian life. I would return to the Army in 1950 and put in enough time to retire by 1968.

Then I would join the civilian workforce for 18 years and finally retire for good. Along the way I became interested in electronics and that became my hobby. On one occasion I picked up a broken computer printer, purchased a repair manual for it and got it up and running. Later I bought a broken computer and repaired it too. A Friend of mine checked out the printer and computer and told me I had them both working. I started to learn how to use this new toy of mine and in time with the help of Friends I knew enough to use it as a word processor.

I decided to put my military career on paper and did so. On 26 January 1995 I finished another story called “FLAK”. In a paragraph toward the end I remembered the B-24 bomber shot in two over Augsburg, Germany.

I would complete my book and call it “The Real Side, World War II & Korea” and thereafter, which was the story of my military career. My World War II stories would find their way on to the 456th Bomb Group web site for the world to read.

On 1 December 2000, a message appeared in the Guest portion of the Bomb Group web site. It was from Jerry Lind saying his Brother Robert had been with the Bomb Group and was shot down over Augsburg, Germany, 27 February 1945. He requested any information from others about that day. I checked my mission assignment sheet and his brother went down on the mission I was on. I checked the 456th BG History Book and the B-24 he was in was the only Group loss that day and it said the plane had gone down when the tail section broke away.

I made contact with Jerry by e-mail and referred him to my story on the web site titled “FLAK” where I described the downing of his Brother’s plane. It was hard to imagine what I had seen that day would mean so much to another person 55 years later.

Jerry is a former Marine and an artist, so he painted a 2 foot by 3 foot painting of his Brother’s plane, and two other B-24’s to represent those who had given him information about that day (Bob Carlin now deceased and me). He gave the painting to the Bomb Group, in memory of his Brother, at the last reunion in Texas.

This past summer Jerry told me he was going to visit the site of our old World War II airstrip in Italy with his son. I emailed him the following:

"Have an enjoyable trip and look in the skies overhead, listen, and maybe you will hear the bomber engines and maybe see a glimpse of the vapor trails now attended by Angels looking after your Brother and the others who gave so much, with tears in my eyes. Bob"

Upon his return he e-mailed me the following:

"Bob I stood there at the headquarters building and overlooked the field. I could almost hear the engines of the planes as they took off and thought of what you wrote to me. And as I listened to the bomber engines overhead I could see the vapor trails attended by angels looking after my brother and all the other crews who gave so much as you said. I could see them clearly even through my tear filled eyes. A moment I will never forget as long as I live. I felt a part of it even though I was not there at the time, but because my brother was, it was so very special."

We must remember that there was nine other crew members who died with Robert that day. As a result of that day, ten families would get the notice from the government that said, “We regret to inform you”, and so it would be until the end of World War II.

Jerry did send me a proof of his memorial painting recently, which I have framed and it is now on the wall of my computer room. We are still in touch.

Note: 1956 to 1958, I was stationed in Augsburg, Germany with the 11th Airborne Division. The US Army specialist (a former Hitler Youth) that I used as interpreter, in the Provost Marshal’s Office, had been on the Flak guns that day trying to shoot us down. We became very good Friends. That man was Karlhans Wiedemann.

On 28 March 2002, I was reading some newsletter sent to me by the CID Association editor. In it I would learn that Wiedemann had become an Army Criminal Investigator, who was well respected. The article said that Wiedemann had died 1 April 2001.

It was 8 May 1945 and I was in Bari, Italy. We had driven by Jeep to the AAF Headquarters there. I was with the squadron intelligence officer since I was his assistant. He greeted us with the news that the Germans had surrendered and all troops were to be confined to their bases. We returned to our squadron expecting to see a great celebration. Someone had a flare pistol and was firing red-red flares over the airstrip. It was as if someone had let the air out of an over-inflated balloon. I think the ground crews celebrated for the air crews. Most of us enjoyed getting a real deep, undisturbed, sleep, the first in a long, long, time. I stopped drinking. There was something to look forward to.

In the days ahead we were offered the opportunity to visit our former targets, at low level altitude, to survey the damage, but I declined. I wouldn't fly unless I had to. Some did go and received more than they had bargained for. The Russians were only on our side, during the war, for their own purpose, and that was demonstrated when they shot at some of the sight-seeing planes, downing two, I heard.

Later we did fly to Udine in north Italy. The bomb bays were closed and converted into containers to carry food. We loaded them with British rations and headed north. The combat missions had taken a toll from our crew, not by wounds you could see, but those which you couldn't see. On the landing approach I found the pilot and co-pilot fighting each other with words and actual blows, even though they were strapped in their seats. I stepped into the space between the seats and told them, that I didn't care if they killed one another, but the crew wanted to get on the ground safely and they could settle their dispute there.

I never did find out what the problem was and didn't care. On the ground I "borrowed" a tin of British Cigarettes. Seeing an Italian nearby, I showed him the cigarettes and said, "Pistol". He left and and came back with an Italian pistol and the swap was completed. We spent the night in Udine. There we were invited into a British Officers' Club. We were treated royally, but were reminded that they were "Aussies" and not "Bloody British" and as long as we didn't make that mistake we were welcome.

June came and it was time to go home. My crew took one of the bombers for the flight to the states. First stop was Algiers. We decided to see the city. In the square was a sight you will never see again. A French Army Band was playing the "Marseilles" one of my favorite national anthems. Walking along the street a group of kids gathered round us, so close I actually kept pushing them away. Little did I know they wanted my Helbros wrist watch and had cleverly removed it. When some American MP's came by and stopped, the kids ran. The MP's told us to be careful that they had just lifted a sergeant's wallet. I checked and found my watch was missing. I was picked up by French Police and taken to the Casbah on the trail of the thieves. The alleys finally got too narrow for the Jeep and it was parked. Two of the policemen headed up a winding narrow alley; the other stayed with me at the jeep. Some of the inhabitants gathered around the jeep and with that the policeman unholstered his pistol. They moved away and the other policemen returned with a suspect, but no watch. I was glad to get out of there.I stayed in billets that night and two crew members stayed with the plane. In the morning we found that the plane had been looted and it was done so expertly that neither man had been awakened. The shoes that one of the men had beside him were stolen. Two parachutes, cigarettes, and the navigator's luggage containing his celestial books. The luggage was nice, but when the thief found the weight of the luggage had been books, it must have been a great disappointment. Later, we found that some of the officers, sleeping in the billet, had their sheets stolen while sleeping on them.

The flight to Dakar was uneventful. We crossed the Sahara Desert and I asked permission to lower the radar dome. I didn't think there would be any ground definition, but was surprised when three peaks showed up in the form of a triangle. Then we headed across the Atlantic to Fortaleza and Belem, Brazil. In south America it rained all the time. I did replace my wrist watch there and bought gifts for the family at home. We continued north to British Guyana; Cuba; and the last stop Hunter Field, Georgia. Guess what the first meal was after being in Italy? Your right, spaghetti.

|

The 456th Bomb Group Memorial, in the AF Museum Garden, Dayton, OH. It was taken by me (Bob Reichard) on a visit there 15 Jun 1994. |

| Table of Contents | Previous Page | Next Page |