Above is Lt. Jules Sachs and his wife, ca. 1944.

Courtesy of 456th Bomb Group Association

Our pilot had to fly as a co-pilot before he could take his own crew. He lost his life while on his checkout flight. As the story goes, they never got over enemy territory. The weather had been bad during that period of time and the need to hit targets great. The bombers wound up over the Adriatic Sea in bad weather, and apparently collided with each other. I think the loss was eleven bombers and one hundred and eleven men that day.

Above is Lt. Jules Sachs and his wife, ca. 1944.

Courtesy of 456th Bomb Group Association

He was flying as a copilot with a veteran crew prior to leading his own crew into battle. He was missing in action on 11 November 1944, while flying from our base near Stornara, Italy, in B-24 bomber #42-51718, from the 745th Bomb Squadron, of the 456th Bomb Group.

As a result of our early misfortunes we were considered a "Jinxed Crew". Our flight commander addressed our crew and told us so. He told us we had to be the best or we were not going to make it.

I volunteered for a mission on 19 Nov 1944, which turned out to be Vienna. I hung around operations and one night it paid off. Capt Miller, Squadrron bombardier, asked me if I would like to go on a mission the next day. My reply was that I had to start sometime, so it might as well be now. He gave me the opportunity to back out. He knew that the target was Vienna. I later learned that the scheduled bombardier was aware of the target and was too close to going home that he wasn't going to take a chance, so if a replacement was found he could stand down. It was an experience, and afterward I was beginning to wonder about my survival possibilities

The pilot couldn't take the AA fire, so he pulled out of the formation, but we did get bombs away. On the ground I knew that pilot was having problems. He didn't bother to tie his shoes and forgot to shave. They finally took his crew from him and assigned him to another crew as a co-pilot. He finally went down behind Russian lines. When he returned later, he had had it, and was transferred elsewhere. I often wondered about him and years later his name appeared on the membership rolls of the 456th bomb group organization. He had formed his own business sometime in the post war era and had become successful. I noticed that he is actively engaged in the organization. A nice ending.

The crew would fly altogether for the first combat mission on 11 Dec 1944. It would be my third mission and the target would be Vienna again.

Standing, L-R: Co-pilot LAY, Pilot SCHLUETER, Bombardier REICHARD, Radio TRANZILLO Kneeling, L-R (gunners): Engineer DALE, Tail PATTERSON, Nose PAINTER, Lower ORAND, Upper WELLS

The B-24 behind us was not our plane. For most of our missions we shared planes with other crews. Finally we received our own plane. It was the latest, a B-24L. We put in extra oxygen bottles, which we had salvaged from Vis Island, and some other items. We never got to fly the plane in combat. It was used by another crew and they left it splattered all over Rumania. the crew bailed out safely and made their way back with Russian help.

Note: By the time this picture was taken, Lt. Sachs, the original pilot of crew 6459, was missing. To this day, he is still listed as MIA on a plaque in the Sicily-Rome Military Cemetary.

The charge of quarters woke us in our tent long before daybreak. It was a cold morning in southern Italy. We dressed and had breakfast, which was probably dehydrated eggs. Then we boarded an open army truck and headed to the 456th Bomb Gp Hq for our briefing. This was my third mission and the other two had been rough. We entered the briefing room and the silence told me the target was a tough one. I looked at the briefing map and the course line was headed to Wien (Vienna). I thought, my God, not there again. My first mission had been to the same city, but the target was different. Today it was the southwest marshaling yard (train staging area). We received our briefing and were told what the enemy opposition would be and since the German Army was pulling back, the closest count of anti-aircraft artillery heavy guns was 500 plus.

Finally we were airborne and the group was formed and we were following the direction of the line indicated in the briefing. There were thirty B-24 (Liberator) bombers, which included those who would return early for mechanical reasons. Seven planes were assigned to each of the four boxes with the extras filling vacant positions. Number one plane was the lead of each box, with number two to the right and slightly to the rear of number one. Number three was in the same relative position, but to the left of number one. Number four was lower and directly behind number one with number five to the right and behind, and number six was in the same relative position, but on the left side of number four, and so on.

We followed the Adriatic Sea north to avoid land based anti-aircraft artillery, gaining altitude to cross the Alps, which was a formidable barrier. After land-fall, one of the group radio operators, who monitored German air traffic, relayed the message that 12 squadrons were ordered to intercept us. We were one of many groups, headed north so the word "us" was all encompassing. Prior to the target the German pilots were engaged by our escort fighters and we proceeded without opposition. That course line, on the briefing chart, which we were flying, came to the initial point and there we turned from a deceptive direction, directly toward our target. This point was usually about 30 miles from the target. For that 30 miles we would head toward the target without veering away from it. The same altitude and airspeed were maintained, regardless of the cost. There had to be a stable platform, so the lead bombardier could give the Norden bombsight a chance to do the upmost damage. The flak was heavy, actually cutting out the sunlight as we entered the area where they were exploding. If the shell was close by when it burst, you could see the initial fire of the shell exploding and then came the smoke. I watched it come ever closer until I realized the next one would do the trick, but that one didn't come.

We were taking hits and one actually sounded as if we had been hit by a truck. Bombs away! I talked myself into crawling forward, on my belly, to look back and see the bombs hit. This wasn't necessary because photos were being taken. By doing so I probably saved my life. I had been in the kneeling position and had I remained there, the piece of flak, which entered the front glass would have caught me on the head or chest. After that hit the plane fell from 26,500 feet. I thought the pilot and co-pilot had been killed by the hit. I got up and tried to use the intercom, but it wouldn't work. I got the attention of the nose gunner and he tried, but shook his head, no. I watched the altimeter unwind as we fell. There was a small opening between us and the pilot's compartment and I could see that the pilot's and co-pilot's feet were still on the rudder bar and they were moving, so I knew they were alive.

I didn't know that one of the engines had been on fire and they had put it out by diving. We stabilized at about 15000 feet. The upper turret gunner had been knocked out of his turret by a piece of flak which had penetrated the azimuth ring, and that caused it to slow down before it entered the rubber gasket of his helmet. The blow actually knocked him out of the turret and the piece of flak stuck in the gasket leaving him with a bruised cheek. No one was injured, but a later check would show the plane had 34 holes.

When we leveled off we were still in sight of Vienna and all alone. The pilot tried to use the radio to call for fighter protection, but it was knocked out. He was trying to maintain altitude, but was losing ground. He gave the command to lighten the aircraft and everything of weight, which hadn't been nailed down went, except our parachutes. The navigator was asked to set a course for Vis Island, in the Dalmatian Group off the coast of Yugoslavia. He set the course against great odds; he was suffering a great discomfort, because he had crapped in his pants during the action. The crash strip was only 3500 feet long and was made of interlocked metal airstrip material. We made it, but the brakes were out, so we had repositioned parachutes on each side of the plane fastened to the waist gun mounts. At touchdown the pilot rang the bail-out bell and we deployed the chutes, which acted as air brakes.

We spent six days there with the Partisans and a dozen Americans who were assigned there.

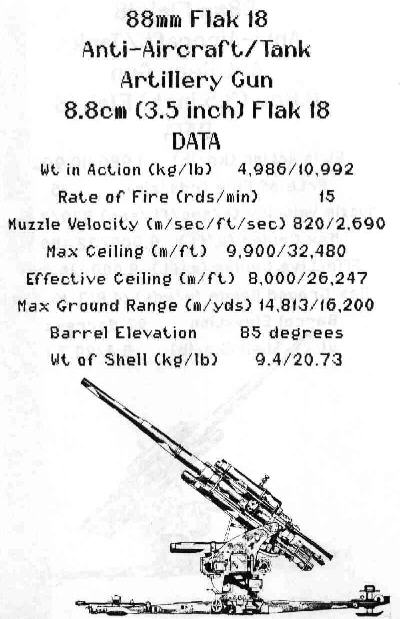

FLAK is the abbreviation of the German word Fliegerabwehrkanone and in English means anti-aircraft cannon (artillery).

Late in 1944 the US Army Air Force fighter planes controlled the skies over Europe. The remaining German fighter planes were engaged before the bombers appeared in their target areas, so that threat was neutralized. However, their anti-aircraft (Flak) batteries were still intact and as the German ground forces retreated from the Russian Armies, they withdrew their guns and used them to strengthen their defenses closer to home.

On 19 Nov 1944 and 11 Dec 1944, I was assigned targets in the Vienna area. Our intelligence had lost track of the number of anti-aircraft guns guarding the city. They said that they had lost count after the number had reached five hundred, so they said there was 500 plus. I flew over the city on those dates and I knew they were right in their assumption. At times the barrage was so intense that the daylight disappeared and it was as if someone had cut out the sun.

|

|

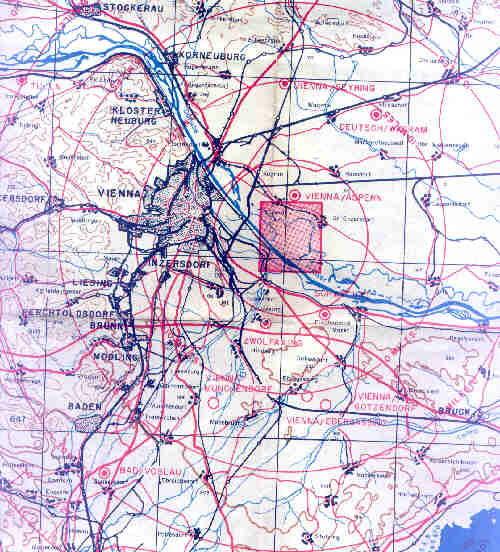

This is a section of the map, from a FLAK Chart/Map from World War II (1944), showing the City of Vienna (Wien). The Red Lines show the coverage provided by the 500 plus heavy anti-aircraft guns protecting the city and its surroundings. A bombing mission here left your future in doubt.

|

The above is a bombardiers target of Vienna (Wien). The target map is from chart No 14-30-NA, compiled & reproduced by 941st Engr Bn, MAPRW, May 1944.

| Table of Contents | Previous Page | Next Page |