Lt. Robert W. Reichard, before shipping out to Italy

The war was dropped on us by the attack on Pearl Harbor. My grandfather's youngest son Edward was stationed near there, at Schofield Barracks. He was serving in the infantry and was not injured in the attack. Prior to the attack, many Americans headed to Canada, not to escape the draft, but to join the Canadian forces who were already engaged in the fighting. I graduated from Lansford High School with the class of '42. Everyone was joining up and I was interested in flying, so the aviation cadet program looked good to me. All I had to do was convince my parents to sign the release to join the cadets, because I was under age. I wasn't making much progress until I convinced them that I couldn't pass the physical because of flat feet. I had the release and headed to the Army Recruiter, at Allentown. I took the physical and I had a hard time convincing the doctors that my feet had never bothered me. After a lot of head scratching, on their part, they okayed me. That was September and it wasn't until March when I was called to active duty.

The first camp was the Nashville Army Air Base. It was a cold, damp place. We weren't issued clothing for about three days, so when I went to bed I had everything on including my overcoat and I was still cold. The barracks were one story buildings with two space heaters to heat them. The heater was well named because it only heated the area around the stove. The stoves burned soft coal and due to the constant inversion, the smoke hung close to the ground and everyone developed the "Nashville cough".

On to the pre-flight at Santa Ana, California. After that, Ryan School of Aeronautics, Tucson, Arizonia for primary flying. The plane flown there was the Ryan PT-22. On to basic flying school, Marana Air Base, which was north of the primary school. The plane here was the BT-13A (Vultee Vibrator), which I soloed and had more than the required tail-spins, but didn't satisfy the test pilots. I was "washed out" and sent back to pre-flight. I was retained in the program and sent to Kingman, Arizonia, where I earned my aerial gunner wings. Next stop bombardier school, Kirtland Field, Albuquerque, NM. I finished that with the class of 44-7 and headed to Lincoln, Nebraska. There the pilots, navigators, bombardiers, engineers, radio operators were brought together and the crews were formed. Next stop was Casper, Wyoming and there we received our combat training in B-24's (Liberators). From there to Topeka, Kansas and our overseas assignment. Some were lucky and picked up their aircraft there and flew them on to their combat station. We were to go by Liberty ship. I had a week free and no money, but I did have the ticket to Camp Patrick Henry Virginia, which was the staging area for the boat ride. I hitched a ride on one of the bombers headed to Manchester, NH and then home. My parents thought I was on my way overseas and they had a nice surprise when I showed up again.

Picture of some of Crew #6459. It was taken at Camp Patrick Henry, VA the end of September 1944. This was just before we boarded the troopship to leave Norfolk, VA for Italy to enter World War II with the 456th Bomb Group.

Back Row Left to right: Bombardier REICHARD, Co-pilot SCHLUETER, Navigator SHUFELT, Kneeling left to right: Nose gunner PAINTER, Engineer DALE

The trip from Hampton Roads to Bari, Italy was as slow as the slowest ship in the convoy. I took on the job as Provost Marshal and as a "hot shellman" on a 4 inch-fifty surface gun,which must have served in World War One. The fixed round weighed 76 pounds. It took 26 days to get to our destination. We did see action after we entered the Mediterranean Sea. It was after Gibraltar and we were alerted that there were submarines in the area. I was talking to the Troop Commander, Capt Hall, and noted that his room was just below the water line, then, the general alarm sounded. I had my duties on the gun, so I was allowed to go to my battle position. The troops were kept below deck. Two of our ships were hit. The tanker was a ball of fire and the only ones who could have survived were the ones, in the aft gun position, if they had jumped when they were hit. In Bari Harbor there were over twenty plus ships sitting on the bottom with their masts sticking out of the water, the result of a much earlier German air raid.

During the night of 2 December 1943 about 30 Allied vessels were being unloaded in Bari Harbor, Italy. When darkness fell, to keep on schedule, lights were turned on. Sure enough, German bombers appeared over the illuminated port at about 07:30 PM and within 20 minutes, without a loss to themselves, left 19 transports sunk and seven severely damaged. Two ammunition ships received direct hits, oil from a severed pipeline mixed with gasoline from a burning tanker, spreading the fire. Over 1,000 workers were killed and the port was several weeks coming back to full operation.

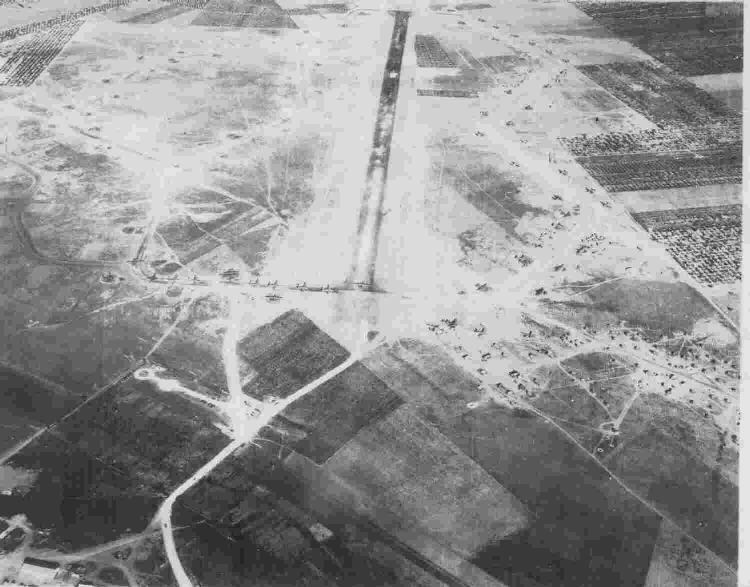

We were located near Cerignola, Italy, close to Stornara. It was a farming area. The 456th Bomb Group (H) was located on a knoll at the SW corner of the airstrip. The airstrip was laid out in a north/south direction. The airstrip was one of the eight satellite airstrips around Foggia, which had been utilized by the Luftwaffe before they were chased out. Foggia was to our north. The squadrons were located around the perimeter of the airstrip. There was the 744th at the SW corner, the 745th at the NW corner, and the 746th and 747th were on the east side. Our ground contacts with each other were nil except for briefings and the resulting combat missions.

We were dispersed in an olive orchard and lived in tents. In fact, upon our arrival, the four officers, were given a pyramidal tent to erect. In time we would move into a tent, which had been upgraded, by a crew who had completed their missions and were on their way home. The upgraded tents had tile floors, stove, shower, and the walls were extended. Everything had been scrounged. The shower stall occupied one corner of the tent and was fed water by a fighter plane drop tank, which had been elevated above the shower head level. A make shift stove heated the water by using aviation gasoline. The main tent heater was a 55 gallon drum which had been cut in half and inverted over a fireproof base. 100 octane gas was allowed to flow in, through metal tubing, from an outside drum and this wound up in an improvised burner. The burner was a metal can filled with sand which had been placed inside the overturned drum. The gas was allowed to drip into the sand after a burning piece of paper was placed in it from a hole in the side of the drum. The chimney was made of empty 88mm casings which had been fired by the German anti-aircraft, when they had been in the area. The tent area was enlarged by untying the side walls, building a wall around tent, big enough to accept the tent sides when they were moved from a vertical to horizontal position. That increased the tent floor space outward the length of the tent wall. The tile floors and walls were usually done by hiring Italian help.

Lighting the tent stove could be hazardous to your health as the navigator learned. He didn't put the lighted paper in the burner first. He turned on the fuel, walked around the stove, struck a match, I yelled, "Stop" too late and he put the match into the stove opening. The result was a loud explosion and a trip to the medics to treat his badly burned arm. The air to gas combustion was bad and that resulted in clogged chimneys. This was overcome by beating on the chimney while the stove was on. The chimney spewed forth burning pieces of carbon which burned holes through the tent tops. As a result it was not unusual to lie in bed at night and be able to study the stars without going outside.

We ate in the mess hall which was a make shift affair of canvas, masonry, and wood. It also served as the squadron officers' club in the evening. The food was of the canned and dried variety and the eggs were dehydrated. (On our missions we carried "K" rations, which were composed of 3 different types: breakfast with canned scrambled eggs, dinner with a can of cheese or canned dog food. These were eaten cold and you had crackers in place of bread. There was a packet containing 5 cigarettes, toilet paper, and other goodies.) At meal time we would have a long wait, so we would play "Hearts" (simple card game) while we waited to be fed. In the evenings we gathered in the club to put our worries aside. It was pot luck as to what you were going to drink, but as long as it contained alcohol it filled the bill. The only mix available for mixed drinks was grapefruit juice aplenty. I hated it and to this day it is not my cup-of-tea. There was a piano and at least one of the officers could play it. When he started playing a group would get together, and oh how they would harmonize. A favorite was "Three Jolly Coachman". I couldn't carry a tune, but I would get in my cups and would join in. The result was amazing -- they would stop singing and stare at me. I would take the hint and go back to my cup.

Our latrine facilities were the many holed outhouse or pipes that had been shoved in the ground, throughout the tent area, so you would urinate in designated places instead of everywhere. (I don't know how the modern army will handle that one with female troopers.) I guess that confined the smell to selected spots. Foxholes were everywhere, but there were too many injuries as a result of falling into them as we left the Club to get to our tents. They were filled in to cut the casualty rate. The tent ropes still took their toll and they couldn't be removed without doing away with our shelter. We had to learn to navigate better.

There was electricity in the evenings, so we were allowed to tap in and put a light bulb in our tent. In the daytime the generators supplied the orderly room, medics, operations, and supply room. I found that electric line draping through an olive tree along side our tent and tapped it. We could now enjoy those dreary fall days writing letters in our tent. That worked fine, but one day we were cleaning outside the tent and one of the party had a machete. And what does one do with a machete in hand if there is a tree nearby? Right, he swings at the trunk for the hell of it. Only this swing was different. It produced sparks much to his amazement, so what to do? Swing again to recreate the phenomenon. He did and there was another display of sparks and our daytime electric power was cut. He had severed the power line tap where it ran down the trunk of the olive tree and into the tent.

There was an Armed Forces Radio Station (AFRS) at Foggia, but radios were few and far between. A select few had recovered some from crashes and put them on line. One tent had a novel setup. They had the ingenuity to stick a wire antenna out the top of their tent and this they connected to a combination of earphone, wire coil, and a razor blade. The result was a unpowered crystal radio which brought in the AFRS Radio Station. The end of the coiled wire had been bent to touch the razor blade and that acted like a crystal.

The main duty was to fly combat missions. When we weren't doing that we were training in the air or on the ground, or pulling different duty officer assignments, which included censoring mail, and MP duty in Orta Nova. They even brought a bombardier training platform which we ran in one of the group buildings. I was glad when I used the last one in Bombardier School, but here it was again. I trained as a radar operator, but never flew a combat sortie as one.

When we arrived at our squadron we were told that our tour would be completed when we had flown 50 combat missions. Missions above a certain parallel of latitude were credited as 2 missions. When I started flying, the targets were all 2 for 1 and I would be going home after 25 times out. That soon ended, and our missions were called sorties and it was 1 for 1 wherever you went and the magic number was 35. Briefings were held in the early morning hours before each raid. They were held at Group Headquarters. A general briefing and the specialized briefings for pilots, navigators, bombardiers, etc. after.

When we returned from the sortie we were interrogated at Group Headquarters, but we picked up a donut and a container of coffee from the Red Cross girls before entering the interrogation building. The girls were great, but they must have been selected because of their homely looks, so the war effort wouldn't be affected. (However our radar training officer dated one and we nicknamed him "Radar" because like radar, he would pick anything up.) At this time we had our chance to report any future targets which we had seen, such as railway traffic build-ups, the number of chutes exiting a disabled bomber, target results, anti-aircraft, Luftwaffe intervention, etc. Back in the squadron the medics issued a 2 ounce shot of American whiskey. It was for medical purposes and they accounted for each 2 ounce by your pay roll signature.

Church services were held at Group Headquarters. . I had developed a strong sense of religion along the way. As an aviation cadet I received a copy of the 91st Psalm and a picture of Christ from a woman in Lehighton, Pa, by the name of Hawk. I think she was the wife of anther cadet who entered the service with me. He became a pilot. I kept them with me and they were my crutch. I read the Psalm nightly and carried it with me always. It was my talisman. I didn't ask God for any favors except, if I had to be hit, do it right, as I didn't want to lie bleeding, in the cold, without aid for the 2 to 4 hours the return trip usually took.

Psalms 91 |

|

He that dwelleth in the secret place of the Most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord, he is my refuge and my fortress: My God, I him will I trust. Surely he shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, and from the noisome pestilence. He shall cover thee with his feathers, and under his wings shalt thou trust: his truth shall be thy shield and buckler. Thou shalt not be afraid of the terror by night: nor for the arrow that flieth by day; Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday. A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee. Only with thine eyes shalt thou behold and see the reward of the wicked. Because thou hast made the Lord, which is my refuge, even the Most High, thy habitation; There shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling. For he shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways. They shall bear thee up in their hands, lest thou dash thy foot against a stone. Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder; the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet . Because he hath set his love upon me, therefore will I deliver him on high, because he hath known my name. He shall call upon me, and I will answer him: I will be with him in trouble; I will deliver him and honour him. With long life will I satisfy him, and show him my salvation. |

We weren't confined to the squadron, but schedules and lack of transportation kept us in the area except for briefings. etc. We weren't allowed to be on the flight line when the other crews returned, so we wouldn't see the dead and wounded being removed. We weren't allowed to carry our side arms into battle. The colonel figured that once we left the plane, in enemy territory, we were prisoners of war and if we had our side arm they would have an excuse to shoot us. I didn't like the idea and I had a Colt Frontiersman, revolver, 32/20, (which I had purchased in Casper, Wyoming), so I carried my own gun. The pilots were the captains of the ships and rightly so. If the mission turned out good, he got the credit. If there was a problem, the finger was pointed at the navigator or bombardier. It was a no win situation for us peons.

One day I received a picture from the movie actress Gene Tierney clad in a Kimona. It was autographed to me. I was dumb-founded because I hadn't written her. The tent was filled with laughs and then I had my answer. The navigator had written her asking her to send a scantly clad photo. Not knowing if there would be any repercussions he signed my name.

The war ended on 8 May 1945. The combat crews didn't celebrate. It was as if the air had been let out of a big balloon and it lay exhausted on the ground. Thoughts turned to the future which we now had.

| Table of Contents | Previous Page | Next Page |